'She of the steel-grey eyes,

Wearing the dreaded aegis, shield which is ageless, immortal.'

- Homer, “Iliad” 2.446-445

Goddess of strategy, invention and the state. Daughter of Zeus and one of the twelve who rule from Olympus. One of the six females to sit among the twelve, yet considered to be the least feminine of the goddesses. One of the few deities to remain a virgin, holding no interest in marriage or romance.

Like most of the other Greek deities, Athena’s stories have been remembered and passed on for centuries and her image continues to be sculpted, painted and represented in a variety of ways, even in Australia. Standing outside of what used to be the first Savings Bank in Australia is a statue of this goddess, hand outstretched, towering over the mortals who walk past her. She stands in a regal, yet welcoming manner, wearing a Greek helmet and a sash across her chest, decorated by a monstrous face and snakes.

This figure is a copy of the 4th century BC bronze statue, probably carved by the Greek sculptor Kephisodotos, known for his statue of Eirene – peace – in the form of a woman holding a child. The original statue of Athena was discovered in Piraeus, Greece in 1959. It is either an original creation or, more likely, a representation of Hellenistic art. Her helmet has two owls on either side, displaying the goddess’s patron animal. Her sash with the snakes and gorgon head is reminiscent of Athena’s shield, Aegis, which holds the severed head of Medusa, killed by Perseus.

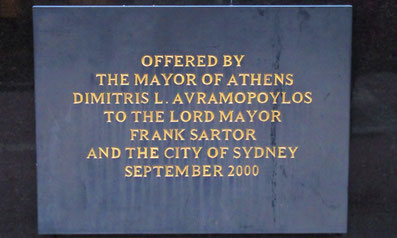

The statue, as told by the plaque below, was gifted to the city of Sydney and Mayor Frank Sartor by the Mayor of Athens, Dimitris L. Avramopoylos. The gift was presented in September of 2000 to celebrate the Sydney Olympics. It stands in front of what is now the Athenian Restaurant on Barrack Street in Sydney CBD. This elegant building, originally a bank, stands as an example of the 19th century, pre-nationalist era, with its imported building material exemplifying its high esteem.

The stories about Athena a vast and varied, but here are a couple to peak your interest. The story of her birth is one of the more unconventional births of Greek mythology, and that’s saying a lot. In an attempt to stop anyone cleverer than Zeus from usurping his throne, Zeus married “cleverness” herself, an Oceanid called Metis. When Zeus found out that his wife’s second child would be the one to overthrow him, he swallowed Metis while pregnant with Athena. This act caused Metis – “cleverness” – to become part of himself. Sometime later, Zeus began suffering from a

severe headache. Depending on the version of the myth you read, either Prometheus or Hephaestus struck Zeus in the head with an axe – cause that’s the scientific way to fix a headache – and out from the gaping wound rose Athena, fully grown and clad in armour, screaming out a war cry. And so Athena was “born”, and the second child destined to overthrow Zeus never came into existence.

Athena thus became known for being the most masculine of female deities. She never concerned herself with affairs of the heart and is perhaps the only Greek goddess to be considered a leader. Though a virgin, Athena did have a child in a typical Greek-myth loop-hole way. The story goes that Hephaestus, god of fire and blacksmithing, lusted after Athena, but to no avail. Eventually, in a desperate attempt to have her, Hephaestus lunged for her. Some part of him – sweat, tears or semen, depending on what version you read – ended up on her thigh. Disgusted, Athena wiped it off with a cloth and threw it to the ground. From this cloth, which held the essence of both gods, sprang a child who Athena took, raised and named Erichthonius. He later became a king of Athens.

Finally, perhaps the most well-known myth of Athena is the one about Arachne. Arachne was a mortal who boasted about her weaving skill, claiming to be equal to Athena herself. This, by the way, is never a good thing for Greek mortals to do. Hearing of these boasts, Athena descended from her throne in Olympus and, in disguise as an old woman (a favourite among Greek goddesses), confronted the girl about her rash claims. Arachne hurled insults at the old woman and challenged Athena herself to a competition. Revealing her divine self, Athena accepted. Both competitors created flawless works. In a rage at this outcome, Athena slashed up Arachne’s face. Instead of living with this visual mark of shame, the mortal girl hanged herself. Seeing the suspended body, Athena took a small amount of pity upon her and turned her into a spider, sprinkling her with poison and allowing her to continue weaving, but at the same time condemning her to hang in order to feel safe.

And so these stories live on. Through centuries of change, as nations rise and fall and cultures shift and alter, Ancient Greek thought and imagery continues to be present in our daily lives, across the globe. The image and memory of one who used to be considered a deity now stands in the narrow passage of Barrack Street, in the CBD of Sydney, thousands of kilometres away from where she was once worshiped.

Bibliography

Peter Miller, “The Athenian Restaurant (Former Savings Bank of NSW),” Flickr, 2012, <https://www.flickr.com/photos/64210496@N02/7170641328>

“Statue of Athene,” The Online Database of Ancient Art, 1995, <http://ancientrome.ru/art/artworken/img.htm?id=1652>

Write a comment